Inspiration

From Shackleton to Mawson: An Expert’s Guide to Antarctica’s Greatest Explorers

When I was the director of the museum at South Georgia in Antarctica, I used to weed Ernest Shackleton’s grave. When we visit Grytviken with A&K guests and come ashore, we go out to the cemetery where he’s buried, and lead a toast to “The Boss” along with stories of Shakleton’s infamous Antarctic expedition aboard ‘Endurance.’

Shackleton first set off with his men to cross the Antarctic from South Georgia. When his ship ‘Endurance’ sank, he managed an amazing 16-day trip on one of its rescue boats (the ‘James Caird’) from Elephant Island across stormy Antarctica seas back to South Georgia — and then traversed it, which was another notable feat. Eventually, Shakleton came back to South Georgia on another expedition in 1922 and died there. So, he’s very much connected to the island.

When Shackleton and his two companions were crossing South Georgia, it wasn’t far as the crow flies, but it was quite a circuitous route between the mountains. They completed it in 36 hours nonstop because they knew that if they stopped and rested, they wouldn’t wake up. On one occasion, Shackleton told them they would have a meal and a rest. After they ate, he let the other two fall asleep. After a few minutes, he woke them up and said, “Right, you’ve had a good long sleep.” They felt better and off they went.

I used to say that my hero was Shackleton because I’ve spent a lot of time in Antarctica on South Georgia and I’ve studied his expeditions, especially the legendary ‘Endurance’ expedition. But as Shackleton became everyone’s hero over the last couple of decades, I decided I needed a new hero.

Thomas Bagshawe at Waterboat Point, Paradise Bay in Antarctica

He’s an Englishman by the name of Thomas Bagshawe and very few have ever heard of him, especially when compared with Shakleton and his famous Antarctic expedition. Bagshawe was on a crazy expedition in 1922 at the age of 19, during which he and another young man decided to spend the winter in the Antarctic. They made a little hut out of an old boat, which they called Waterboat Point, where they lived for a year. They not only survived in Heroic-Age conditions, but they performed an amazing amount of science, everything from weather readings and ice charting to studying geology and the breading habits of penguins. I think the reason they survived was because of their sense of humor. Despite experiencing appalling conditions, whether getting absolutely frozen or soaked, and even after their ferocious arguments, they’d just collapse laughing and somehow managed to see the funny side of things.

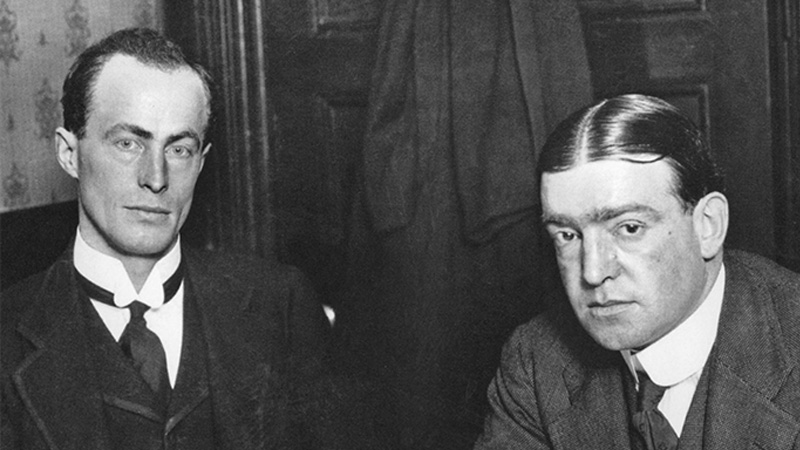

Douglas Mawson (left) and Ernest Shackleton (right) circa 1906

There are a dozen or so other fascinating expeditions from the Heroic Age of Antarctic exploration (from 1892 to 1922) that many people don’t know about. One of the standouts getting more attention these days is Douglas Mawson. He’s an Australian who completed an unbelievable solo trek in 1912. He’s also the subject of an award-winning 2007 documentary, Mawson: Life and Death in Antarctica.

In the documentary, you learn that Mawson was sledging with two companions in a place on the Antarctic continent known as the home of the blizzard. Both companions died and Mawson didn’t have enough food to complete his trek. Still, he wanted to get as close as possible so that he and the daily diaries they’d been keeping would stand a better chance of being found by a search party. At one point, he fell down a crevasse, but was tied to his sledge and the sledge luckily got stuck at the top. He managed to pull his way up using the rope when suddenly the edge of the crevasse broke off and dumped him down and at the end of his rope, again. It must have been pretty shattering. He entertained giving up and knew he’d only need to undo the buckle, which would send him straight to the bottom and an instant death. But he thought no, because he had a fiancé waiting for him at home. With incredible effort and an even stronger mind, Mawson managed to climb up and get out onto the surface—again. He could not recall how long he lay there on the surface recovering, but eventually he managed to put up his little tent and eat.

There are so many stories like this in Antarctica that are all about mind over matter.

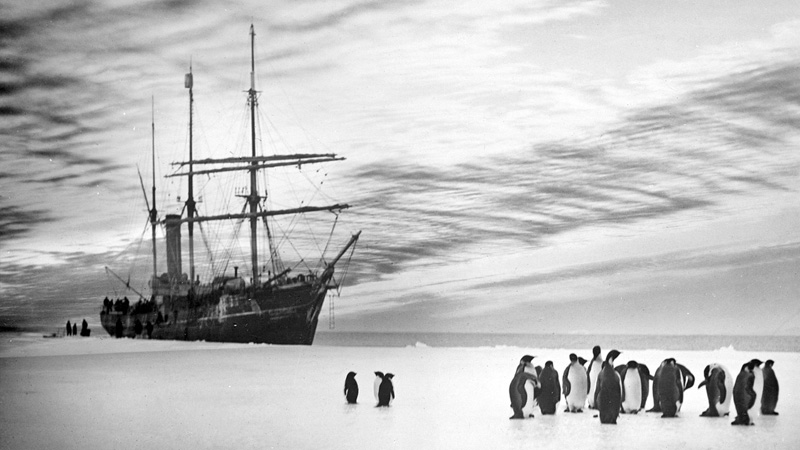

Mawson’s 'Aurora,’ anchored to an ice floe off Queen Mary Land during the First Australasian Antarctic Expedition

The Americas

The Americas Europe, Middle East and Africa

Europe, Middle East and Africa Australia, NZ and Asia

Australia, NZ and Asia

The Americas

The Americas

Europe, Middle East and Africa

Europe, Middle East and Africa Australia, NZ and Asia

Australia, NZ and Asia